We use cookies on this site to enhance your experience.

By selecting “Accept” and continuing to use this website, you consent to the use of cookies.

Search for academic programs, residence, tours and events and more.

Aug. 12, 2021

Print | PDFChris Nighman’s research agenda lies at two important junctures in the history of communication: the transition from manuscript to print culture in the 15th century and the current digital revolution.

A professor in the Department of History at Wilfrid Laurier University, Nighman calls himself a “revisionist historian.” Nighman uses digital technologies to re-examine texts that are hundreds of years old to get a sense of changing intellectual world views in the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance periods.

Nighman at the transi tomb effigagy of Richard Foxe at Winchester.

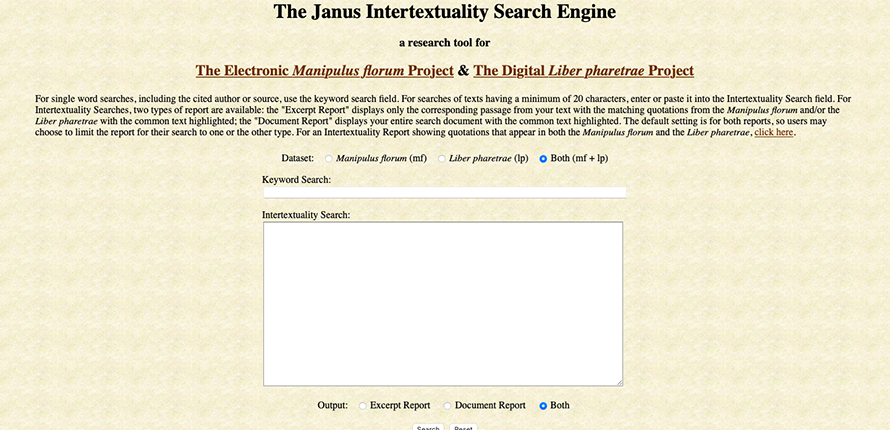

In addition to producing his own body of scholarship on European intellectual and cultural history, Nighman is building digital tools that others can use to advance their own teaching and scholarly endeavours. In 2008, he launched the Janus Intertextuality Search Engine, which was designed to allow scholars to compare a medieval or early modern Latin text with the Manipulus florum, a book of quotations compiled during the 14th century.

Through a simple search query, users can seek specific passages and discover the origin of influential quotations. Nighman has since expanded the search engine’s database to include another collection of quotations, Liber pharetrae. These anthologies are known as “florilegia.”

We asked Nighman to share his research inspiration, findings and future plans.

How did you first become interested in this work?

CN: "My doctoral thesis was on a series of sermons that were delivered at a big church conference called the Council of Constance, which met from 1414 to 1418. It was kind of like an academic conference for theologians, bishops and abbots. While editing the sermons of Richard Fleming, who went on to become the Bishop of Lincoln, I was struck by his confidence in identifying quotes by philosophers like Seneca or Augustine. His sermons were full of quotations and the way he was saying them reflected a certainty that these quotes were original.

"But, in fact, they weren’t. I realized that Fleming owned a copy of the Manipulus florum, which is a book of quotations. It means 'a handful of flowers.' Each quotation is a beautiful blossom. When I searched through it, I found that many of the quotations he used had been paraphrased, manipulated, miscited and changed in various ways. This opened up a whole new world to me of the transmission of authoritative quotations.

"The Manipulus is the most important of these collections of quotations from the Middle Ages and had never been edited. I then thought that putting it online as an open-access tool would be of great service to scholarship and the academic community. I’ve been working on it off and on since 2001."

What is the Janus Intertextuality Search Engine?

CN: "The Janus search engine was designed to allow myself and other scholars to compare a medieval or early modern Latin text with the Manipulus florum. I named it after the Roman deity Janus, who looks both forward and backward, because the search engine can reveal the influence of earlier texts on the Manipulus and the influence of the Manipulus on texts written after its composition in 1306.

"When I conceptualized Janus, which was built by two computer scientists at the University of Waterloo, it was a groundbreaking innovation. We launched the search engine in 2008 and in 2010 a similar intertextual search engine for Latin scholarship was created in Australia. Then another appeared in Europe in 2015."

How did you come up with the idea for the Janus search engine?

CN: "Its inspiration came from turnitin.com, a website that reviews student work to prevent plagiarism. In 2006, I was baffled by a student whom I had just caught plagiarizing. I had warned the class to not test the machine because the machine would win, and yet one student cut and pasted directly from Wikipedia.

"As I pondered why that student would ever do that, I began to think of my own work. Then it occurred to me that this was the exact kind of search engine I needed to compare large texts to the Manipulus florum.

"Once Janus was in place, I started working on another medieval florilegium, the Liber pharetrae, which means the 'book of the quiver.' Each quotation is like an arrow aimed at exactly the topic one would like to address."

Did the use of digital tools influence your research focus?

CN: "I think so. When I added the Liber pharetrae to Janus, I thought it would be interesting to see how it overlapped with the Manipulus florum because I am certain that Thomas of Ireland, the author of Manipulus, did not use the Liber pharetrae. Using the Janus search engine, we can say that although the texts didn’t influence one another, there is still overlap.

"This allows us to get closer to what was considered a 'commonplace' – a widely recognized proverb or short quotations – during that era because two, three or four different compilers of florilegia independently agree that certain quotations are worthy to include. The larger the database, the keener sense we have of the intellectual culture of the time. That’s a research question that never would have occurred to me without the technology."

What are you working on now?

CN: "I’m in the final stages of developing a website for my Chrysostomus Latinus in Iohannem Online (CLIO) project. John Chrysostom was an important Christian saint of the late fourth century in the Greek church and patriarch of Constantinople itself, kind of like the pope of the Orthodox Church. Over the centuries, his commentary on the Gospel of John was translated from Greek into Latin three times and the various translations are significantly different from one another. What we’ve done for the CLIO project is present all three Latin versions of the text side by side, plus a highly revised version of the second translation, so users can compare each version and look at the original Greek text from the 1728 edition.

"I also recently received a five-year Insight Grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada that will fund approximately a dozen student research assistants, who will help me develop online editions of two more Latin florilegia for Janus by 2026. One of the most rewarding aspects of these digital projects has been the chance to work with many excellent student research assistants: more than 25 since 2003. They have all gained income and experiential learning opportunities while contributing to the advancement of scholarship."

This article was adapted from The Bridge, a Laurier Faculty of Arts newsletter written by Eric Story.