We use cookies on this site to enhance your experience.

By selecting “Accept” and continuing to use this website, you consent to the use of cookies.

Search for academic programs, residence, tours and events and more.

Feb. 26, 2021

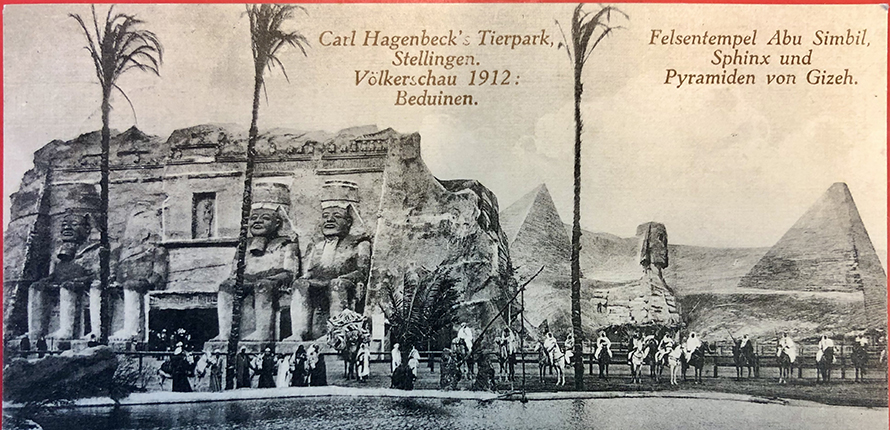

Print | PDFIn the late 19th and early 20th centuries, human traders exhibited “exotic” people from other parts of the world in living dioramas as a form of mass entertainment. These human zoos were primarily built in European countries “with colonial aspirations” such as Germany, Austria and France says Judith Nicholson, an associate professor of Communication Studies at Wilfrid Laurier University.

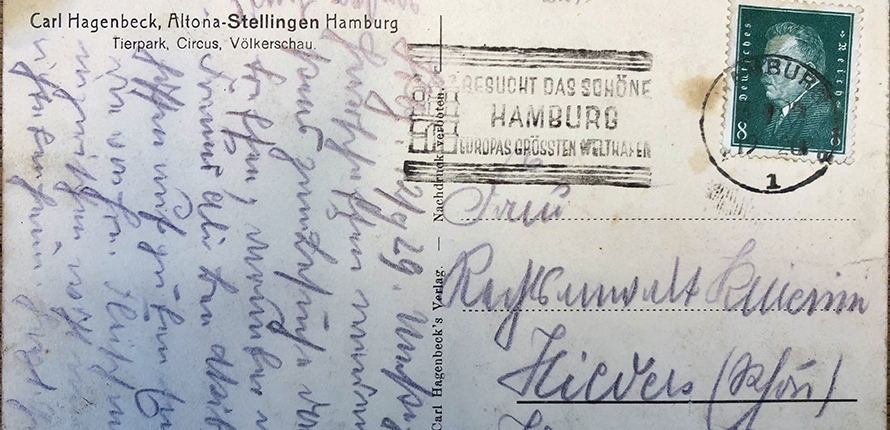

The rise of human zoos coincided with the early advancement of photography and many images of the exhibits are printed on postcards preserved from that period. Though time and progress have revealed human zoos to be degrading and exploitative, Nicholson is studying the messages written on the backs of these postcards to learn more about the historical context in which they existed.

Photo credit: SHMH Altonaer Museum

How did human zoos come to be?

JN: “Human zoos were established around 1875 and their establishment is often linked to Carl Hagenbeck, a German animal trader. He bought exotic animals for many decades, bringing them to private zoos and circuses. At a certain point, Hagenback started to bring in Indigenous peoples from all over the world and discovered that there was a great interest in seeing exotic humans. It was at a moment in the late 19th century when industrialization was happening in Europe and more people had leisure time and a little bit of spending money. Ordinary people who did not have the money to travel could have the world come to them.”

What did a typical human zoo look like?

JN: “There was usually a series of thatched huts set up on a fairground and different types of people grouped together. You would have people from places like Africa, northern Canada or Russia set up in individual villages that visitors could come and get close to. You might see a traditional wedding dance being performed for visitors, but people also lived in these places. These villages were their homes for months or years, so we have voyeuristic snapshots of people doing routine activities such as washing their clothes or breastfeeding.”

Participants were actually made to live inside these dioramas?

JN: “Yes. There were contracts which were typically signed by human traders, not by the exhibited individuals, and they were not allowed to leave. Of course, that changed over the decades because the exhibited people learned local languages. They fell in love. Their children were schooled there. So eventually the boundaries dissipated a little bit, which perhaps contributed to the disappearance of human zoos.”

Photo credit: SHMH Altonaer Museum

What do you see when you look at photographs of human zoos?

JN: “It’s unnerving for me as a Black scholar to look at images of people being objectified who could very well look like my cousins, in some instances. Often, we’re looking at European visitors who are dressed in their finest clothing juxtaposed with individuals in an exhibit who are in traditional costumes and various degrees of undress. You see the tensions of spectating and performance.”

You travelled to Austria and Germany in 2019 in search of human zoo postcards. Tell us about your trip.

JN: “In Austria, we interviewed a collector who has nearly 3,000 human zoo photographs and postcards. He let us photograph both sides of the postcards since my research is focused on messages on the back. It was actually difficult for us to find places with the content we were looking for, but eventually we found a small museum in Germany that has more than 30,000 uncatalogued postcards. The archivist pulled out just 42 for us and they were all relevant to my work. I would love to go back and look at more.”

In your research so far, have you found much connection between the images on the front of human zoo postcards and the messages on the back?

JN: “The short answer is no, they have nothing to say about the images on the front. And it shouldn’t have surprised me because scholars of postcard studies have found the same thing. For example, there is a genre of postcards from the turn of the 20th century that feature images of mostly African American men being lynched. And on the reverse side, nothing about the horrific crime, but messages along the lines of, ‘I was in whatever town, I had a nice visit’ as if they had purchased a postcard showing an image of a local church.”

Photo credit: SHMH Altonaer Museum

Does that indicate that in the historical context, images such as these were seen as ordinary and acceptable?

JN: “It could be, but it’s hard to say. I’m trying to stay open as I do my work. Perhaps it’s that this was such difficult knowledge to deal with that people sidestepped it. Some scholars have said that because of the brevity of postcards, much of the message is in code that only the sender and receiver understand. So there may be messages about what’s on the front and we’re just not able to decode them yet.”

What are you learning as you read these postcards?

JN: “I’m observing how the movement of people overlaps with the movement of postcards, which overlaps with the movement of colonial interests. When Germany, for example, went to the Namibia area, there was exploration and colonization, animal trade and human trade, and postcards being sent. It was a route that was constantly overlapping.”

Can you draw any contemporary parallels or insights from human zoos?

JN: “Human zoos feel like a metaphor for the incarceration of Indigenous and racialized folks. Because of our legacy of colonization, there is an unevenness in how people are treated and looked at that can and does prejudice others. How can we change that gaze? My human zoo postcards project is about how we can look differently from our perspective in the 21st century at other forms of incarceration.”